I invited my buddy, Garry Rodgers, back to TKZ for a fascinating behind-the-scenes trip to the morgue. He’ll hang around for questions/comments, so don’t be shy. Now’s your chance to ask an expert something you might need for your WIP. Enjoy!

Most living people never visit the morgue.

Most never think of the morgue except when watching TV shows like CSI or some new Netflix forensic special. The screen may show in hi-def and tell in surround sound, but it can’t broadcast smell. That’s a good thing because no one would tune in and the actors would be looking for real-life morgue jobs like homicide cops, coroners and forensic pathologists.

I did two of those real-life morgue jobs for a long time. I’m a retired murder cop and field coroner who spent a lot of hours in that windowless place. Now, I’m a crime writer and thought I’d share a bit of what really goes on in the morgue with my crime-writing colleagues.

The morgue is strictly off-limits for anyone not having a specific reason to be there. That’s for a few reasons. One is the place can hold sensitive court evidence. Two is that it’s a somewhat disagreeable place due to the odor, temperature and the continual chance of contracting a contagious disease. The third reason is dignity. Even though the majority of the morgue occupants are no longer alive, they’re still human entities and not some sort of a morbid exhibit.

The morgue is a place of business. It’s a medical environment where the deceased are stored, processed and released to their final disposition. The morgue operates 24/7/365 as death pays no attention to the clock or the calendar. But, the morgue is busiest between 8:00 am and 4:30 pm Monday to Friday—holidays exempted. Morgue workers need time off like anyone else.

A city morgue, like I worked at in Vancouver, British Columbia, is an active environment. It has a dedicated shipping and receiving area with a loading dock much like a typical warehouse. Bodies arrive by black-paneled coroner vans or on sheet-covered gurneys brought down from the wards. They’re booked into a ledger, assigned a crypt and, yes, marked with a personalized toe tag.

Vancouver General Hospital’s morgue is like Costco for the dead. Stainless steel refrigeration crypts, stacked three-high in two rows of nine, have shelving for fifty-four. The freezer unit stores eight and isolation, for the stinkers, can take six sealed aluminum caskets or “tanks” as we called them. These tanks are also used for homicide cases, locked to preserve forensic evidence.

A grindy overhead hoist shifts cadavers from wheeled gurneys that squeak about fluorescent-lit rooms, touring them to and from roll-out metal drawers. Refrigeration temperatures are ideally set at 38-degrees Fahrenheit (4-degrees Celsius) while the ambient range in the autopsy suites is held at a comfortable 65 / 18. The storage rooms, laboratory and administration areas are normal office temperature, and they’re set apart from the main morgue region. Support staff, for the most part, have no sense of being so near to the dead.

Operational personnel in the morgue are highly-trained professionals. The workhorse of the morgue is the autopsy technician or attendant called the “Diener”. It’s a term originating from German that translates to “Servant of the Necromancer”. Dieners have the primary corpse handling and general dissection responsibility. They do most of the cutting.

Hospital pathologists are primarily disease specialists. They spend the majority of their day in the laboratory peering into microscopes and dictating reports. It’s a rare general pathologist who stays with an autopsy procedure from incision to sew-up. Usually, hospital pathologists come down to the morgue once the diener has removed the organs and has them ready for cross-section.

A hospital pathologist takes a good look for what might be the anatomical cause of a sudden or unexplained death. The main culprits are usually myocardial infarctions, or “jammers” as they called in the heart attack word. Aneurisms are another leading cause of dropping dead, and they’re often found in the brain.

Hospital pathologists sometimes do partial autopsies when they want to confirm an antemortem diagnosis. That might be a certain tumor or the extended effects of a runaway respiratory disease like Covid19. Sometimes, there’s no clear cause of death such as in a heart arrhythmia or a case of toxic shock.

Forensic pathologists are an entirely different animal. These are meticulous medical examiners with a tedious touch. It takes years of specialized training and understudy to become a board-certified forensic pathologist qualified to give expert evidence in criminal cases.

Forensic autopsies are peak-of-the-apex procedures inside the morgue. In a setting like Vancouver General Hospital (VGH), there are six autopsy stations in one open room. At any given time, the slabs are occupied and there more in the pipe. Not so with a forensic procedure.

There are two segregated and dedicated suites for forensic autopsies at VGH. Protection of the corpse, which is the best evidence in homicide cases, is paramount. So is maintaining continuity of possession, or the chain of evidence, that ends up in court. In a forensic autopsy, there’s utmost care to ensure the body is not compromised by contaminating it with foreign matter like DNA or losing critical components like bullets or blades.

In a homicide case, the body is taken from the crime scene in a sterilized shroud and locked in a tank. There’s an officer or coroner appointed to maintain continuity from the time the cadaver is bagged until the corpse is laid out on the slab. This is a critical element in forensic cases and one that is treated as gospel.

A forensic pathologist stays with the autopsy from the time the body is unlocked from its tank till the time the pathologist feels there is no more evidentiary value to glean. This is usually a full-day event but sometimes the body is put back in the tank, held overnight, and the process goes on the next day. This completely depends on the case nature such as multiple gunshot or knife wounds.

There are police officers at every forensic autopsy. Those are the crime scene examiners who photograph the procedure and pertinent physical properties. Detectives receive evidentiary exhibits like foreign objects such as fired bullets or organic particulates. There might be semen samples or other questionable biological matter. Then, there are usual suspects for toxicology examination like blood, urine, bile, stomach contents and vitreous fluid.

Radiography is done in almost all forensic autopsy cases. A portable X-ray machine scans the body as it lies on the table. In some situations, MRI / CT technology is helpful.

But, nothing beats the eye and experience of a seasoned forensic pathologist. They observe the slightest details that even a general pathologist would miss. However, don’t dismiss what a good diener can spot. It’s a treat to watch a forensic pathologist and a diener work when they’re in synch.

At day’s end, folks in the morgue are much like anyone else. They have a market to serve and they do it well. They’re also prone to talk shop in a social setting. There’s nothing like having drinks with a diener who’s into black humor.

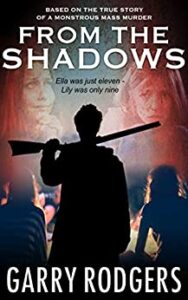

What if six members—three generations—of your family were slain in a monstrous mass murder?

FROM THE SHADOWS is part of Garry’s “Based on True Crime” series. Available on Amazon and Kobo.

I couldn’t write a piece about what really goes on in the morgue without a few war stories. In my time as a cop and a coroner, I’ve been around hundreds of cadaver clients. Maybe more like thousands, but I never kept track. There were a few, though, that I’ll never forget.

One was “Mister Red Pepper Paste Man”. My friend Elvira Esikanian, a seasoned forensic pathologist of Bosnian descent who cut her teeth by exhuming mass graves, is a gem. She also has a wicked eye for detail.

I brought this old guy into the morgue after finding him dead in his apartment. Neighbors reported him screaming like someone was skinning a live cat. They rushed in and found him collapsed on the floor. No idea what killed him, but no sign of foul play.

Elvira opened his stomach and it was positively crawling. She knew what it was—botulism. Elvira told me to go back to the scene and look to see what he’d been eating. I found it. It was a jar of red pepper paste that was years past its expiry date, and the inside was a mass of organic activity.

Then, there was Kenny Fenton. He was found dead after being dumped beside a rural road and left to rot for a week in hot weather. I brought him into the morgue as intact as possible but it wasn’t easy. Kenny went into a stinker tank before Dr. Charlesworth could take him on.

As a routine, Kenny had a radiography session before his dissection. It showed a bullet in his gut. Not a run-of-the-mill bullet, of course. It was a .22 short with no rifling engraved on its sides.

Turns out, Kenny was accidentally shot in the neck by a Derringer dueling pistol. The bullet cut his carotid, hit his spinal cord, bounced back to his esophagus and he swallowed the dammed thing before bleeding out and dying fast. The crew he was with thought it was better to dump Kenny than report it.

And I can’t wrap up without a bit of spring foolishness that went on in the morgue. It involved my buddy—Dave the Diener.

Dave had about thirty years in the crypt before he met me. In fact, Dave had something to do with me getting hired by the coroner’s office because he thought I might be a good fit. Dave may, or may not, have been right.

It was the First of April and a Friday morning. Dave liked Fridays because he usually left early once his cutting was done. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that, and I’ve done it myself.

But this Friday was different—probably had something to do with the date. I snuck into the morgue real early and prepared Dave’s first case. I needed some weight so he wouldn’t suspect anything off the bat. I put a bunch of concrete patio blocks on the crypt’s drawer base. Then, I placed my cadaver inside a shroud and laid it on top. I even attached a toe tag and made the right entries in the ledger.

I wasn’t there but sure heard from the other staff who were in on it. Dave rolled-out his first subject-for-the-day and unzipped the shroud. Smiling at Dave was the puckering face of a blow-up sex doll.

That’s the kind of stuff that really goes on in the morgue.

Garry Rodgers has lived the life he writes about. Garry is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner who also served as a sniper on British SAS-trained Emergency Response Teams. Today, he’s an investigative crime writer and successful author with a popular blog at DyingWords.net as well as the HuffPost.

Garry Rodgers has lived the life he writes about. Garry is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner who also served as a sniper on British SAS-trained Emergency Response Teams. Today, he’s an investigative crime writer and successful author with a popular blog at DyingWords.net as well as the HuffPost.

Garry Rodgers lives on Vancouver Island in British Columbia at Canada’s west coast where he spends his off-time around the Pacific saltwater. Connect with Garry on Twitter and Facebook and sign up for his bi-monthly blog.

Neat, Garry. Sue, thanks for bringing him on.

I had no idea about the Dieners. I wonder what they tell friends and family when training. An MD doing a pathology residency sounds impressive and neutral. But, “I’m going to community college to learn to be an autopsy technician” might get a lot of strange looks. Maybe even more than “training to be a mortician.”

Important and valuable work, however. So hang in there, any autopsy technician trainees who might be reading this.

My pleasure, Eric. Garry’s posts fascinate me.

Thanks, Eric. As far as I know, there’s no accredited school for Dieners. It’s a thing you have to learn on the job. And, there’s a lot to know about it. I’ve seen newbies make a real mess of the incisions and extractions and some pretty upset funeral directors trying to patch up.

Wow, Sue. Thanks for this post. And thanks to your friend. More than I ever wanted to know about morgue shenanigans…but so interesting, I’m keeping it around for possible tidbits. 🙂

Great idea, Deb!

Nice to be here as a guest, Deb. I’m a regular lurker but Sue was kind enough to ask for to say something. BTW, black humor is a realty in the world of cops and coroners. 🙂

Garry, having worked a bit in law enforcement in a different life, been there. And in the medical field-the best of both worlds…

And last but least, the t-shirt with “Cremation-think outside the box”. (My husband’s two cents worth). Again, thank you for such an informative and fun *ahem* post. 🙂

“Cremation – Think Outside the Box” – Haven’t heard that one before 🙂

Thanks, Sue and Garry for all this helpful information. 🙂 — Suzanne

So glad you enjoyed the post, Suzanne. 🙂

Nice to hear the info was helpful, Suzanne!

Thanks so much for hosting me, Sue. Nice to be in such esteemed writing company 🙂

Anytime, my friend. xo

Question: We’ve all seen the moment when the next of kin is brought into the cold, sterile storage place and they pull out a drawer, and she looks down and says, “Yes, that’s him” (or even better, “I don’t know that man!”)

Isn’t that mostly myth? Isn’t ID mainly done by showing the kin a photo?

In my experience, James, that’s a myth. In all my morgue time, I’ve never brought a family member inside the shop. If there was an identification needed, we’d remove the body from the morgue and the plastic shroud and take it to a ward where it would be in hospital blankets on a stretcher. Seeing a loved one in that cold, clinical morgue setting would be emotionally devastating. Traumatizing for the morgue staff as well. Thanks for asking – good question!

Oops. Guess I have to rewrite the scene in my novel where the widow insists on seeing the body of her murdered husband and her lawyer-cousin pulls strings and she gets her chance in the morgue.

Thanks, Garry and Sue! An excellent education with a nice shot of humor.

Garry, what are the best techniques for dealing with the smell? Vicks Vapo Rub in the nostrils? At the end of the day, how do you get the smell out of your nose/mouth/lungs/mucus membranes?

Very good question, Debbie. I gotta tell a little Vics VapoRub story. Early in my career, I was involved in recovery of a crashed plane that went down in thick trees and wasn’t found for 11 days in hot weather. There were six decomposing bodies trapped inside and I was the guy who had to crawl in and remove them. The smell was absolutely putrid so I used a tactical team gas mask and put Vics in the filter. Yes, it knocked back the smell somewhat but, to this day, one whiff of Vics makes me want to puke.

You never really get past the smell of decomposing remains. The best approach is an N95 mask and get in and get out as quick as possible. In the morgue, we used EZ-Breather power-vented / oxygenated hoods because we’d be with the body for a couple hours at least.

One last smell story. I made the mistake of wearing an expensive leather jacket into a stinker scene. The odor went right into the leather pores and I had to throw it away.

Good morning, and thank you for the fabulous guest post!

.

I have a few questions, if that’s okay.

.

1. How are the dead moved about? I’ve seen the gurney in use on TV of course, but moving the dead bodies from one place to another – is there a portable crane or something? I’ve seen patients with severe disabilities picked up out of their beds and moved to gurneys, and later from the gurney to a bed in the same fashion – a portable manual crane. This was especially the case for patients who were obese and just too heavy to handle in any other way. I’m wondering how a 400lb corpse would be moved around.

.

2. What happens to a body that is never identified or claimed by a relative / friend? On TV shows I’ve seen some kind of public burial site” used. Is this the case in real life? Are they just cremated?

.

3. If a body is claimed / identified by family, the embalming and all that happens after the body’s time in the morgue? Done at a funeral home elsewhere? I know little about the process of embalming but I do know there is a lot of liquid pumped into the body… I wonder if the body wouldn’t have a serious leaking issue after a session with a coroner.

.

I had a story going with a scene in a morgue and so this post is gold! Thanks again! I can pick that story up again and add a few of these details.

And a good morning to you, Carl. Hope all’s well on your end. As for your questions…

1. Most modern morgues have a travelling overhead hoist to do the heavy lifting. When a cadaver is brought into the morgue by a stretcher or a gurney, it’s normally raised with the hoist while it’s exchanged onto the roll-out drawer and then slid into the cooling crypt. Removal is the reverse process if it’s going out to a funeral home or crematorium. Autopsy transfer is a bit different because the PM suites are in a different building section from the refrigeration unit. The body is rolled to the “slab” and then usually manually slid from the gurney to the table. If it’s really heavy, there’s an overhead hoist in the autopsy area, as well.

One of my colleagues had a indoor death scene where the victim was 500+ lbs. There was no way of conventionally removing that guy so the pathologist attended the scene and detached the limbs so the corpse could be taken out in lighter pieces.

2. Unidentified / unclaimed bodies are fairly common. Our jurisdiction would hold them in a freezer unit for one year and then bury them in a lot owned by the coroner service. They are never cremated without NOK permission.

3. Embalming is always done at a funeral home / mortuary. The morgue has no equipment for embalming and it’s not a coroner responsibility. Yes, it’s almost useless to try embalming a body that had had a full autopsy.

Glad to hear this piece was some help!

Thanks, Gary, for guest posting today. Nothing like insider knowledge to make a place like the morgue come to life, and the anecdotes you shared were great.

“…morgue come to life.” 🙂

Unintentional puns are the best 😀

Luv the pun, Dale. Thanks for reading and commenting 🙂

Thanks Garry and Sue for this post. It’s very timely for me since my WIP has a scene in a morgue. I basically used “TV knowledge” since I’ve never been inside a morgue myself, and I imagined the police commissioner’s reaction to the smell, temperature, and constituents therein.

I do have one question: in my book, the murder victim’s spouse has been out of the country and arrives two days after the body is discovered in order to identify him. I have her being escorted to the morgue by the police commissioner where the coroner has the body covered on a slab ready for viewing. Is that a reasonable scenario?

Thanks so much. And btw Garry, congratulations on living in Vancouver. I ran the Vancouver marathon some years ago and it was the most beautiful race I’ve ever run. My husband and I are determined to make it back there one day and spend time in that glorious part of the planet. Maybe we’ll take in the morgue while we’re there. ? On the other hand…

You betcha, Kay. Glad you enjoyed the post. 🙂

Hi Kay. Thanks for your question. I mention to James Bell in the previous comment that I’ve never brought a family member inside the morgue for a “viewing”. It’s just too cold and clinical a place for emotional encounter. The scene would be more likely that the commissioner and the coroner had a previous discussion and the coroner had the body in a suitable viewing room and presented on a hospital gurney and covered in a hospital blanket. The experience of seeing a loved one rolled from a crypt and wrapped in a plastic shroud and then unzipped to show the face would be… nasty.

Nice to hear you liked Vancouver. It really is a spectacular setting but it’s also very congested and expensive. Hope you can visit again some day after this virus thing is put to rest. BTW, I wouldn’t recommend ending up in the morgue 😉

Love this post. Nothing gets me going more than bad forensics in mysteries and man, the morgue seems to bring out the worst in writers.

By the way, I had a denier in one of my books. He started out as a walk on but ended up holding a big clue!

Thanks, Kristy. I’m with you on bad forensics 🙂 I rarely, if ever, watch the CSI-type shows but I do read a few books that get it right. Kathy Reichs is one who comes to mind as well as Sue Coletta ;). The little bit I’ve read of Patricia Cornwell also seems factual. I have a retired deiner friend who’s a big Cornwell fan. If I’m not mistaken, Ms. Cornwell was an actual deiner, not a pathologist and she’s been in the trenches. I have to smile thinking back to the old TV show Quincy and him doing autopsies in a white lab coat 🙂

Awww…thanks, Garry. 😀

Hi, Garry and Sue! My WIP is a historical mystery. Do you know when embalming first took place?

Hey, Rebecca! When does the story take place? Embalming has a fascinating history. Check out this article: https://americacomesalive.com/2010/08/03/wars-drive-advances/

If your story isn’t set in the U.S…

The earliest known preserved bodies in Europe are about 5000 years old. These bodies were covered in cinnabar to preserve them. They were found in Osorno, Spain. Embalming dead bodies was unusual in Europe up to the time of the Roman Empire.

Hi Rebecca – thanks for reading this and commenting. I have no experience with embalming but I’ve been in mortuaries and have a rough idea of the process. Basically, it’s draining arterial and venous blood and replacing it with a preservative like formalin or formaldehyde. I think the current technique is several hundreds of years old but the act of preserving bodies through ancient embalming and mummification procedures is many thousands of years in the making. Here’s a link to a blog post I wrote titled “The Lost Art of Making Mummies”. http://dyingwords.net/the-lost-art-of-making-mummies/

Thank you both so much for this post. I have a question for my WIP which involves the recovery of remains where they have lain submerged for 20 years in the shallows of a northern river. I want to set it up that the adult female victim was pregnant at the time of her death, and that a sharp-eyed recovery diver saw additional small bits of bone and collected them from the river. It would suit my plot for the ME to be unable to determine pregnancy for certain (gives my heroine something to work out for herself), but my question is: is it plausible the fetal remains would at least be shown to her in a photograph so she would know of their existence? Thanks again.

Hi Margaret – I just found your comment here on TKZ and we’ve already connected on FB. I’ll post my FB reply here so other KZ followers can get the info. Thanks for the great question!

“It’s conceivable, Margaret. It would really depend on the circumstances of who was involved in the investigation. It’s rare that a pathologist who did the autopsy / medical exam on the remains would have direct contact with the NOK. The investigating police officer or coroner would be the point of contact releasing information and they would exercise discretion / caution in showing photos of the remains. I would think photos would only be shown in extreme circumstances. After 20 years, photos wouldn’t help in identification so in all likelihood, the information about pregnancy would be given verbally or it would be in the autopsy report which the NOK has the right to have.

Also, after 20 years, even preserved in cold water, there wouldn’t be much organic matter left from the fetus – but there would be skeletal evidence provided the baby was far enough along to have a distinct skeleton. Hope this helps!

Pingback: Top Picks Thursday! For Writers & Readers 05-07-2020 | The Author Chronicles

Pingback: Three Links 5/9/2020 Loleta Abi | Loleta Abi Historical & Fantasy Romance Author & Book Blogger for all genres